1. Oude Nonnenklooster

Our walk begins at the bend of the Grimburgwal and the Oudezijds Achterburgwal at the Gasthuispoort. Here we stand at the site of Amsterdam's oldest convent: St.-Mariënveld-ten-Nieuwenlichte, also known as the Oude Nonnenklooster. The grounds lie just outside the city - a dangerous place for a community of women. So the sturdy gate, later replaced by the Gasthuispoort, is locked at night.

A group of some forty women lead a pious and simple life here, inspired by the Modern Devotion. In 1393, they transform themselves into a “real” canonesses’ convent. This poses a problem for some of the inhabitants. To enter this “elite” convent, one must pay a considerable dowry. Most do not have the money for that. Approximately thirty of the forty women therefore leave for other communities. The Oude Nonnenklooster buys land nearby for them. Thus, the island of monastic buildings on the Wallen has begun.

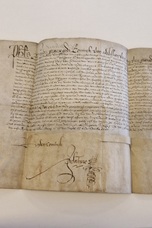

A picture of one nun from the monastery exists.

2. Nieuwe Nonnenklooster

From the Gasthuispoort, we walk toward the Rokin. All the buildings on our left have been grounds of the Nieuwe Nonnenklooster. Founded between 1402 and 1406, it is also a canonesses’ convent and is officially called the St.-Dionysius-ter-Leliën. A dowry must also be paid here. The nuns have a chapel and gardens, a priest's house, and a guesthouse for passersby. With the income from renting out this guesthouse they make a living. In 1578, both the Oude and Nieuwe Nonnenklooster are also disbanded. However, the one hundred nuns from these convents are permitted to remain on the grounds.

Over the centuries, all sorts of things are built on the former convent grounds: a plague house, a gentlemen’s lodgings, a carpentry yard, a city bank, and a home for elderly men (hence: the Oudemanhuispoort [literally: 'Old man house entry gate']. Today, the grounds are owned by the University of Amsterdam. Lectures are held here, and on the Rokin you can visit the magnificent Allard Pierson. This internationally renowned museum, which houses the University’s special collections, is well worth a visit. But for our walk, we will turn right just before reaching the Rokin: this takes us into a tiny alley called Het Gebed Zonder End (The Prayer Without End).

3. St. Claraklooster

This alley runs across the grounds of the former St.-Claraconvent. Some of the women who cannot pay the required dowry for the Oude Nonnenklooster live here. Sometime between 1394 and 1397, they become a tertiary convent: a community with less strict rules than a real monastic order.

For women at this time, life is not easy. Young women from higher circles are often forcibly married off, or sometimes kidnapped and raped. Moreover, in the countryside, poverty is dire. Girls depend on the income of their fathers or husbands. An independent life is virtually impossible for women. This makes entering a convent attractive. Such a community offers security, sufficient food, and also spiritual nourishment.

For the residents of the St.-Claraconvent, this changes after the Alteration. Their buildings are demolished and replaced by houses and workshops. The Gebed Zonder End is the last trace of this place where – day and night – there was always something to pray about. Now, the restaurant Captain Zeppos is located halfway down the alley. It is still an atmospheric haunt of theologians and religious scholars, but folks on walking tours are certainly also welcome there.

4. St. Mariaklooster

We turn left at the end of the Gebed Zonder End toward the Nes. There we come across the grounds of the St.-Mariaklooster, of which nothing more can be found now. In 1415, the grounds of this tertiary convent ran all the way to the Rokin. In the nineteenth century the last buildings were demolished and replaced by the present premises.

We walk right, into the Nes. In the fifteenth century, you would now have been surrounded by monastic buildings right next to each other along this road. And, back in the day, that regularly caused problems.

5. St. Barbaraklooster

From our location on the Nes, the first side street on the right is Sint Barberenstraat. This is named after the St.-Barbaraklooster, which stood here as of 1425, on land obtained from the Oude Nonnenklooster. The nuns of the St.-Barbaraklooster rented out houses and received money from wealthy Amsterdam families.

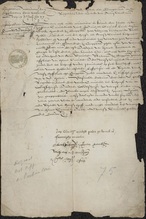

From one of them we know the story.

St.-Barbaraklooster has been feuding with St.-Maria-Magdalena-op-het-Spui-klooster for nearly a hundred years. This other convent sits at the other end of Sint Barberenstraat. The trouble begins when the Maria Magdalenaklooster builds a church right next to St.-Barbaraklooster. The mood becomes so tense that a common gateway has to be replaced by separate entrances for each convent: they cannot pass peaceably through the same doorway. The St.-Barbaraklooster then tries to build a church abutting the Maria Magdalenaklooster. That plan fails. Later on, the St.-Barbaraklooster is responsible for a significant water damage at the Maria Magdalenaklooster. Now the quarrel is so intense that the city council intervenes. In 1485, the St.-Barbaraklooster is dissolved and demolished. The street name, Sint Barberenstraat, is the only remaining indication of its existence here.

Here you are faced with a choice. Walk down Sint Barberenstraat to the other party in the border dispute, the convent St.-Maria-Magdalena-op-het-Spui. Or take the longer route and walk a little further along the Nes, passing two other monastic sites.

6. Cellebroedersklooster

Here, choosing for the latter, we walk along the Cellebroerssteeg until we reach the Wijde Lombardsteeg. The Cellebroedersklooster is located between these two alleys from 1440 to 1578. This site extends all the way to the Rokin.

The friars, following the Rule of Augustine, care for the sick – especially plague victims. They only take care of men; we meet the Cellezusters later on this walk. The monastic grounds also include a cemetery, where plague victims, among others, are buried. This creates a problem after the Alteration in 1578, when the buildings are demolished and the land goes up for sale. Nobody wants a plot where plague victims are buried! Despite the housing shortage in Amsterdam, it takes a long time before the land is sold. Eventually, people assume that the location is no longer dangerous.

7. St.-Margrietenklooster

A little further down the Nes, we find Amsterdam’s Flemish Cultural Center, De Brakke Grond, on our right. We are at the halfway point of the walk, so this Flemish eatery could be a nice place for a break. The Margarethaconvent, also known as the St.-Margrietenklooster stands here as of 1406. Originally founded as a community of women, the group eventually joins the Third Order of Francis. A monastic community housing both men and women is established on the site. The entire property is divided in two, so men and women do not interact. In 1462, the men move to another monastery, so all the dividing walls can go. The women then have the space to themselves until the Alteration. After this, they may continue to live there, but the convent becomes a meat hall, a farmer's fish market, and the inn De Brakke Grond. That name refers to the swampy ground of the Wallen. The little square and the present building stand on the remains of the convent.

We turn right and at the Oudezijds Voorburgwal, turn right again, and walk on until the Stadsbank van Lening [Municipal Loan Bank].

8. St.-Maria-Magdalena-op-het-Spui

What eventually becomes the Stadsbank van Lening [Municipal Loan Bank] building is first the north wing of the convent St.-Maria-Magdalena-op-het-Spui. Founded between 1406 and 1411, this convent was originally a sister community. After a while, the sisters move to the Third Order of Francis. Later on, they follow the rule of Augustine and officially become nuns.

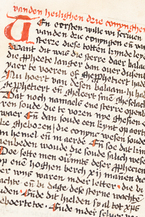

St.-Maria-Magdalena-op-het-Spui is a good example of how religious communities often develop. It often begins with a group of religious, like-minded people who found a religious community together in a house – often a house of Sisters or Brothers of the Common Life. Most convents and monasteries in Amsterdam started in this way, influenced by the Modern Devotion. Over time, these communities usually undergo a process of further regulation, often through the Third Order.

Do you want to know more about the St.-Maria Magdalenaklooster and what has happened in the vicinity of its ornate gateway?

We will discover what a Third Order convent is at our next stop across the water: the St.-Agnesklooster.

9. St.-Agnesklooster

For many years, devout prayers are offered at this site where academic ceremonies are now held. The only remnant of the St.-Agnesklooster or Agnietenklooster is the Agnietenkapel, which is now a part of the University of Amsterdam. But the Agnietenkapel is not the convent’s original chapel. In 1452, the convent is consumed by the great city fire. It is not until 1470 that a new chapel is built - the one we see here today.

At the time of its founding in 1397, St.-Agnesklooster is part of the Third Order of Francis. This is no surprise. Virtually all brother and sister communities are incorporated into the third order fairly soon after their founding as Tertians and Tertiaries, respectively. These communities are not actual monastic communities, but communities of lay people who live a religious life without taking all three monastic vows.

To show that you live in a monastery or convent, clothing is important. Not much is left of the clothing from these early years. Yet, excavations in the Agnietenkapel do yield a piece of clothing.

Do you want to know which piece of clothing it is?

We walk along the water until we see hotel The Grand on our right and pause in the courtyard. Here, two convents were located close together.

10. St.-Catharinaklooster

As of 1412, the St.-Catharinaklooster can be found between the St.-Agnesklooster and the St.-Ceciliaklooster. Although the inhabitants begin as lay sisters, they transfer to the Augustinian order around 1460. They take the three perpetual vows in order to do so and are now officially nuns, also called regular canonesses. From then on, the religious house is a real monastic community. No traces of it remain.

Life according to the Order of Augustine is stricter than life in a convent of the Third Order of Francis, which is a tertiary convent. The vows of poverty, obedience and chastity are not taken by everyone in this latter context. Six religious houses in Amsterdam change to a “regular order,” thus becoming real monastic communities. The vast majority of religious communities on the Wallen remain part of the Third Order of Francis. Something can still be seen of another monastery on this site.

11. St.-Ceciliaklooster

Even in medieval Amsterdam, one cannot live on prayer alone. Money is needed for the survival of the monastic communities in Amsterdam. So too for the St.-Ceciliaklooster. As of the mid-fourteenth century, nuns live on the spot where hotel The Grand now stands. There is almost nothing left of the convent itself. Almost nothing, but if you look closely at the left side of the roof when you walk into the courtyard, you can see an original tower from the convent with a mermaid wind vane.

The sisters of this convent have several sources of income. Like many other monastic communities at the time, they earn their money by renting out houses. For example, they own eight houses on the Oudezijds Achterburgwal. They also lease land just outside Amsterdam. But the sisters also roll up their sleeves and work hard. They have a herd of cows outside the city. And they are not the only ones. Similarly, the sisters of the convent of St. Mary Magdalene-in-Bethany own oxen, which they fatten for the archers' meals. In short, to support a convent or monastery, you need a lot of land.

To find out how the St.-Ceciliaklooster managed to achieve this

We walk back a short distance, turn left, and cross over to the Spinhuis, located diagonally to the left on the other side of the Oudezijds Achterburgwal canal.

12. St.-Ursulaklooster

As we just saw with the St.-Ceciliaklooster, monastic communities have to engage in various activities to sustain themselves financially. We find another good example of this with the St.-Ursulaklooster. This convent, founded at least before 1419, is home to some 65 nuns. Today, on the spot where the convent used to stand, you will find the Spinhuis [spinning house – a correctional workhouse for women]. Almost nothing remains of the convent itself.

The sisters at St.-Ursulaklooster work hard for a living – and they do it cleverly. With different sources of income, for a long time they manage to rake together the money that they need to make ends meet. Much of their income comes from renting out houses in the city. They also lease land outside the city. In addition, they rent out spaces in the convent itself during economically difficult times. One of their tenants is very special: the Surgeon’s Guild of Amsterdam. They organize the first public anatomy lesson in this convent in 1550.

Do you want to read more about this special lesson?

We walk on to the Walloon Church.

13. Paulusbroederklooster

Before their official foundation, the Paulusbroeders [St. Paul’s Brothers] live in a small house on the Nes. In 1409, they obtain a place here on the Oudezijds Achterburgwal to establish their convent. The Waalse Kerk [Walloon Church], still on view in its full glory today, is the original chapel of the abbey of the Paulusbroeders. The Paulusbroederklooster belongs to the Third Order of Francis. It is one of the few male religious houses of the Third Order. As a result, it automatically directs as many as eighty Third-Order religious houses for women. And to think that there were always only ever a few brothers living in the Paulusbroederklooster at a given time!

Despite this great task, the Paulusbroeders find enough time to provide for themselves. They quickly expand their territory and build houses to rent out. Their property becomes so large that an orchard is even established. The city looks wistfully at that large expanse of land. Slowly but surely, the monastery experiences economic decline. Beginning in 1532, the friars have to sell and lease pieces of land. In 1579, the Paulusbroeders see that things can no longer go on like this and leave the monastery.

What happens next for the friars?

A little further on, we turn onto Barndesteeg and walk over to number 6B, the last remnant of the next religious community.

14. St.-Maria-Magdalena-in-Bethanië

Amsterdam is full of religious communities in the mid-fifteenth century. The city council therefore has no appetite for the establishment of more of them. Nevertheless, a proposal is made for a convent to give “fallen women” another chance at a virtuous life. Because prostitutes and beggars are numerous in Amsterdam at that time, the city council agrees. For some time they have been at a loss on this matter. The city government does not know what to do with all of these sinful women in the city. They are often locked up under city gates and bridges.

Thus, between 1450 and 1460, the Convent of St.-Maria-Magdalena-in-Bethanië, also known as the Bethaniënklooster, is founded. And indeed, here the fallen women are given the chance to turn their lives around. Then something remarkable happens: the convent quickly becomes popular among wealthy nuns. In 1462, there are already 220 nuns living there. The sisters live a pious life together, pray and fatten oxen for the archers' meals.

Do you want to know more about the life of one of these converted sisters?

Should we want to catch our breath over a drink, we could now stop in at De Bekeerde Suster [The Converted Sister], on the other side of Barndesteeg on the Nieuwmarkt.

We continue on our way down the Oudezijds Achterburgwal. A little further ahead, turn right onto the Bloedstraat. At the corner intersecting with the Gordijnsteeg, a small statue of a monk rests high up on the wall.

Tip: Walk down Bloedstraat until you reach the Waag, and read the next piece there. That way you won't disturb the ladies behind the windows. This Waag, by the way, is where the Surgeon's Guild settled after starting out at the St.-Ursulaklooster.

15. Minderbroederklooster

City fires, plague epidemics, poverty, and floods: Amsterdam's monasteries and convents on the Wallen endure a great deal. However, it was one particular event that became fatal to most of the monastic communities; namely, the frequently mentioned Alteration of Amsterdam in 1578. In that year, the entirely Catholic city government is deposed and replaced by a largely Protestant government. This means the end for the monasteries and convents. Most monastics receive compensation and, in many cases, board, lodging, and maintenance for life.

There is one notable exception: the residents of the Minderbroederklooster are expelled from Amsterdam without pardon in 1578. And there is a reason for this. The Duke of Alva comes to Amsterdam after the Iconoclasm. He fights hard against the rising tide of Protestantism in the Netherlands – also in Amsterdam. To this end, he settles in the Minderbroederklooster. He founds the Raad van Beroerten [Council of Troubles] to persecute Protestant heretics. The Friars Minor play a significant role in this persecution. After the Alteration, they cannot count on much support from the city council.

One statue, however, witnessed it all. Curious about that story?

We turn left toward the striking Chinese temple on the Zeedijk.

16. Cellezustersklooster

We end our walk on the Zeedijk at the last monastery built on the Wallen in the fifteenth century. On that spot now stands the Buddhist He Hua Temple. In 1475, a group of ten women asked the city council if they could start a Cellezustersklooster. However, the city officials have little interest in the establishment of this monastic community. They would rather use the land for business premises and residential buildings. Since the sisters are going to be engaged in caring for the sick, the council agrees anyway. Another plague epidemic has just broken out and all help is welcome. The sisters stay there until 1582.

It is to be more than four hundred years before nuns walk these grounds again. After the departure of the Cellezusters, the convent buildings are converted into residential buildings. These remain standing until after World War II. By this point, they are slated for demolition. Only in 2000 does the site get a new destination: Queen Beatrix opens the Chinese Buddhist temple where we now stand. Again nuns walk around here, now pioneers from another religion. This shows that religion is still alive and kicking in Amsterdam.

Read more about the He Hua Temple

While you read, you can sit down at one of the many Chinese restaurants on the Zeedijk, for example. Or get a Zeedijk sandwich at butcher shop Vet, which is famous in Amsterdam.