A small group of Anabaptists gathered in a house at the Zoutsteeg where they burned their clothes and ran naked into the streets of Amsterdam. Many illustrations have since been made depicting this remarkable incident.

Location

Unknown house

Zoutsteeg

Religious community

Anabaptists

Object

Engraving of naked Anabaptists in front of a burning house

Maker and date

Anoniem (naar Barend Dircksz.)

1614

Visit

The engraving can be found in: Lambertus Hortensius, Van den Oproer der Weder-dooperen (Enkhuizen 1614)

The Naked Runners Incident of 1535

In 1548, Lambertus Hortensius first published his polemical history of the “Uproar of the Anabaptists.” Decades later, the account was translated into Dutch and published together with several anonymous engravings. These illustrations were based upon a series of sixteenth-century paintings (now lost) by the artist Barend Dircksz., which were commissioned for Amsterdam’s medieval Town Hall. Hortensius’s book is one of many that includes the tale of a small group of Anabaptists who have come to be known as the “Naked Runners” (Naaktlopers).

On February 10, 1535, seven men and five women met in a house along the Zoutsteeg. They listened to the teachings of the tailor Henrick Henricxz. Snyder, who claimed: “I have seen God’s power, God’s person, and spoken with Him. I have been in heaven and in hell.” He instructed the group to remove their clothes and throw them in the fire. They then took to the streets and called out to their fellow Amsterdammers: "Woe, woe, the wrath of God is coming." They were seized and brought to prison. Even there, they resisted instructions to get dressed. The men were executed by beheading on February 25 and the women met the same fate on May 15, 1535. Hortensius’s account and others like it used sensational early Anabaptist events as an example to warn against heresy and fanaticism.

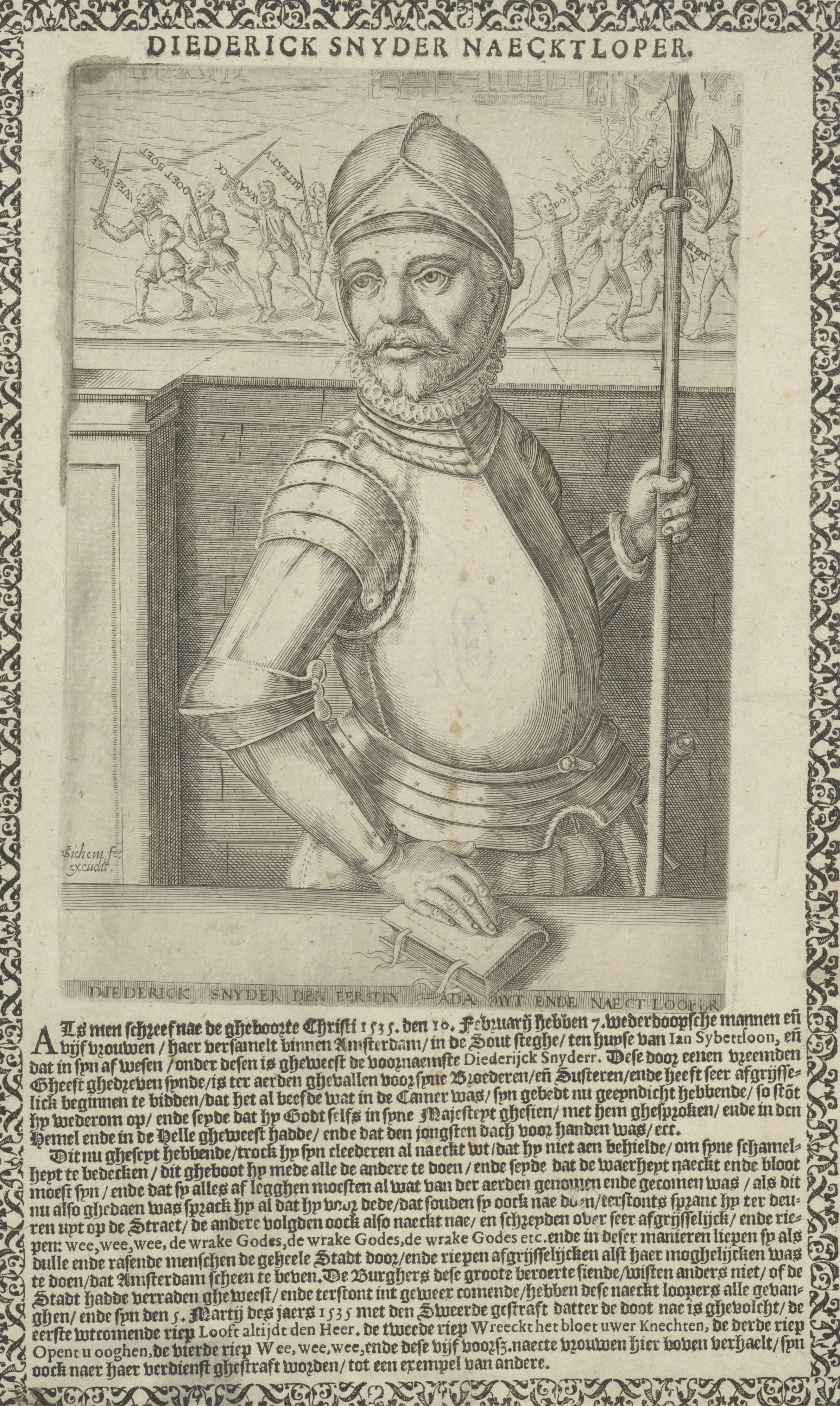

An image of the leader of the Naked Runners is included in a set of illustrations by Christoffel van Sichem, which highlight the “arch-heretics” of the Christian tradition. Since there was no known portrait of this Anabaptist ringleader, Van Sichem invented a likeness for him just as he had done for most of the others represented in this series. While Henrick Henricxz. Snyder is shown in armour, the naked Anabaptists are depicted in the upper right side of the engraving

heretic

Adherent or promoter of heresy (false doctrine). A negative designation for someone who no longer believes in the “true religion.” A founder of a false doctrine is also called an arch-heretic or heresiarch.

Anabaptists

The term Anabaptist, or “Wederdoper” in Dutch, was a derogatory name meaning “rebaptizer” given to a sixteenth-century Christian movement that practiced adult baptism. Since rejection of infant baptism was considered heretical at the time, the name implied the group was unorthodox. At present, globally, the name “Anabaptist” has been reclaimed as an umbrella term for the movement by many (but not all) groups who stem from this movement, including the Mennonites (Doopsgezinden), Amish, Hutterites, and Brethren in Christ.

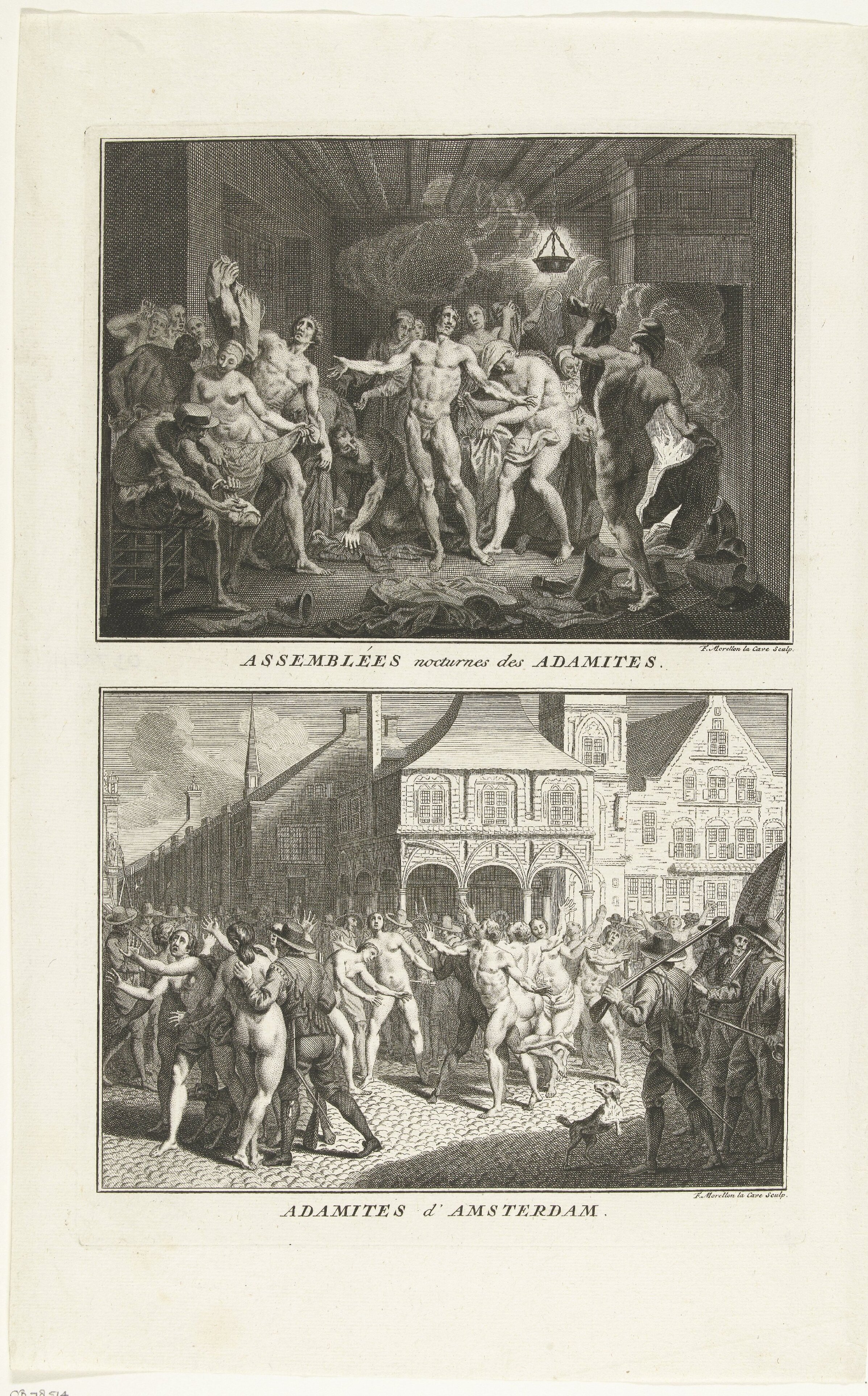

Bernard and Picard also make mention of the Anabaptist naked runners in volume IV of their multi-volume study on the religious ceremonies and customs of all the religions in the world. Detailed engravings show the Anabaptists burning their clothing and also their capture on the streets outside. Interestingly, these are not in the treatise on the Anabaptists and Mennonites; rather, they appears in the next treatise, which is on the so-called “Adamites.”

Adamites

Groups throughout history who supposedly went naked for religious reasons. The term is highlighted in various early modern works on religion and heresy; however, the historical accuracy of lumping together the various named examples in such works has since been challenged.

Anabaptist beginnings involved a diverse range of leaders, groups, and viewpoints. The descendants of the early Anabaptists, the Mennonites and Doopsgezinden of the Dutch Republic, very actively rejected association with all events and people connected to the most apocalyptic, violent, and infamous groups of their theological forebears – including the likes of the Münsterites, the comparatively harmless naked runners, and the small group of revolutionary Anabaptists who briefly took over Amsterdam’s town hall in 1535. Stories of the executions of these Anabaptists are, for instance, intentionally excluded from the Mennonite martyr books and various other confessional history writings.

Dutch Anabaptist Beginnings

The Anabaptist groups which began to emerge as of 1525 in the Swiss Cantons, and also developed in other parts of early modern Europe, were remarkably diverse. The belief in adult baptism was generally held in common, but views on the relation between Bible and spirit, eschatology, and ecclesiology differed substantially. Anabaptism began to spread in the Low Countries – and also in Amsterdam – as of 1530, developing within a context of anticlericalism and reform sentiment that had already started to develop. That year, Jan Volkertsz. Trypmaker, a disciple of the Anabaptist Melchior Hoffman, arrived in Amsterdam and introduced Anabaptism to the city.

Martyrs Mirror

This is the colloquial name given to a volume of Mennonite martyr stories which was published in 1660 and then published again in a second illustrated edition in 1685. These volumes are the most extensive and well-known today, but they are based on a much longer Mennonite martyrology publication tradition. The sixteenth-century stories were first circulated as songs or letters and later as published volumes - each larger than the last. Execution of Anabaptists in the Netherlands began almost immediately after the establishment of the movement in 1530. Persecution intensified in 1535, after the whole movement was tarnished with a bad name in the wake of riotous activities of some revolutionary groups in the Low Countries and the Westphalian city of Munster.

Münsterite Anabaptists

A group of apocalyptically-oriented Anabaptists (many of Dutch origin) who were active in the Westphalian city of Münster. There, a particular Anabaptist theology with an emphasis on the end times had been articulated by Bernhard Rothman, which was eventually adopted by the city. Munster was briefly an Anabaptist Kingdom led by Jan van Leyden until its fall in 1535. Many Dutch Anabaptists flocked to Munster in the early 1530s. Münsterite emissaries like Jan van Geelen also went out into the Low Countries, spearheading a variety of uprisings there, including the attack on Amsterdam’s town hall in 1535.

Nina Schroeder-van 't Schip

Art Historian & Mennonite Heritage Specialist Doopsgezind Amsterdam

Last edited

September 26, 2025

Anonymous, after Barend Dircksz., The Naked Runners in Amsterdam, 1535, engraving in Lambertus Hortensius [I. M. P.; trans. anon.], Van den Oproer der Weder-dooperen (Enkhuizen: Jacob Lenaertsz Meyn, 1614) 18. Collection Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Exterior: photography Our Lord in the Attic Museum.

Sichem, Christoffel van, Diederick Snyder, the first Adamite and Naked Runner [den eersten Adamyt ende naect-looper], 1608, engraving in C. van Sichem, Historische beschrijvinge ende affbeeldinge der voorneemste hooft ketteren (Amsterdam: C. van Sichem, 1608). Collection Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Morellon La Cave, François, after Bernard Picart, Assemblées nocturnes des Adamites and Adamites d'Amsterdam, 1721-1723, etching in Bernard Picart’s Ceremonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde (J.F. Bernard: Amsterdam, 1723). Collection Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Bernard, Jean François, and Bernard Picart, Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde: representées par des figures dessinées de la main de Bernard Picard; avec une explication historique, & quelques dissertations curieuses. Vol. IV (Amsterdam: J.F. Bernard, 1736) 212.

Hortensius, Lambertus,, Het Boek D. Lamberti Horensii van Montfoort, in sijn Leven Rector van de Schole tot Naerden. Van den Oproer der Weder-dooperen. Eerst Inst Latijn beschreven/ ende Ghedruckt tot Basel met Privilegie van de Keyserlijcke Majesteyt. Ende nu in Nederlandts overgheset. Mitsgaders Een Voor-reden van den selven Autheur aen de E. Wijse ende Voorsienighe Heeren / Burghemeesteren Schepenen ende Raedt der Stadt Amsterdam. (Enkhuizen: Jacob Lenaertsz. Meyn, 1614).

Regteren van Altena, I.Q., “Doove Barend, de schilder en de Wederdoopers,” Jaarboek van

het genootschap Amstelodamum 22 (1925) 111-123.

Schroeder, Nina, “Das frühe Täufertum in Kunst und Bildkultur während der Niederländischen Republik (1581 − 1795),” Ulrike Arnold and Hans-Jürgen Goertz trans., Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter 77 (2020) 45-72, 50-60.

Sichem, Christoffel van (I), Historische beschrijvinge ende affbeeldinge der voorneemste hooft ketteren... (Amsterdam: Christoffel van Sichem, 1608).

Zijlstra, Samme, Om de ware gemeente en de oude gronden: geschiedenis van de dopersen in de Nederlanden, 1531-1675 (Hilversum: Verloren, en Leeuwarden: Fryske Akademy, 2000) 133-138.

Online sources

Naaktlopers te Amsterdam, 1535 (website Rijksmuseum)

Last visited 18-09-2025